Previous find of the month

September 2015

To Define What Is Obscene

Objectionable Publications Ordinance 1958

Canberra has long been seen as a progressive city, but even the most freethinking population can be divided when it comes to some issues. In 1954, when the Attorney-General's Department began drafting a new "Obscene Publications Ordinance" for the ACT, it sparked four years of sometimes-fiery debate within the ACT Advisory Council.

The file documenting these debates, 'A3452/999 - Obscene & Indecent Publications' is ArchivesACT's Find of the Month.

Prior to self-government in 1989, the Commonwealth Government created laws on behalf of the ACT Administration. These ordinances often replaced old New South Wales legislation that the Commonwealth had retained when it established the ACT in 1911. After 1911, amendments made by the NSW Government to NSW Acts did not apply to those same Acts as used in the ACT.

While the Commonwealth created legislation for the ACT, it did not mean the ACT Administration had no say in the drafting process. From 1930, the ACT Advisory Council would debate and advise the Minister for the Interior on each proposed draft Ordinance.

"Is Likely to Encourage Depravity"

Up until 1970, the Commonwealth Department of Trade and Customs and its Literature Censorship Board were responsible for monitoring and censoring publications imported into Australia. Prohibited literature included works considered blasphemous, indecent or obscene, or in the opinion of the Customs Minister, unduly emphasized matters of sex, horror, violence or crime and were "likely to encourage depravity."

However, first-class mail (letters up to 370g) was outside Customs' scope, providing publishers with a loophole. Overseas publishers would send master copies of literature, which Customs would otherwise confiscate, to local publishers for printing and distribution within Australia. To close the loophole and regulate local publications, each State Government introduced laws to cover locally produced literature.

During the ACT Advisory Council meeting on the 19th of July 1954, William Byrne noted that legislation with regard to obscene and indecent publications in the ACT was under review. At the time, the ACT was still operating under the old NSW 'Obscene and Indecent Publications Act 1901' (PDF ![]() 362Kb). NSW, as well as Victoria and Queensland, had substantially revised their Acts in 1954 resulting in the need to update the ACT's ordinance.

362Kb). NSW, as well as Victoria and Queensland, had substantially revised their Acts in 1954 resulting in the need to update the ACT's ordinance.

Byrne, commenting on the newly introduced state laws, noted:

"There are, broadly, two schools of thought on this: whether we should follow what has been done in Queensland where a Literature Censorship Board was formed, or whether we would merely amend our legislation to define what is obscene."

On the 20th April 1954, the Queensland Government had passed 'An Act to Prevent the Distribution in Queensland of Objectionable Literature' (![]() PDF 3.39Mb). While NSW and Victoria relied on the judicial system to determine if a publication was obscene, Queensland created a Literature Board of Review to whom the public could submit complaints. The Board would consider complaints under the Act and could prohibit a publication from circulation, making its sale and distribution an offence. Distributors could appeal against the Board's rulings in a Court of Petty Sessions.

PDF 3.39Mb). While NSW and Victoria relied on the judicial system to determine if a publication was obscene, Queensland created a Literature Board of Review to whom the public could submit complaints. The Board would consider complaints under the Act and could prohibit a publication from circulation, making its sale and distribution an offence. Distributors could appeal against the Board's rulings in a Court of Petty Sessions.

During the following Advisory Council meeting on the 9th of August 1954, Ronald M. Taylor asked the obvious question of his fellow members, "What do you classify as an obscene publication?" adding, "I haven't seen any indecent or obscene publications. Do they exist in Canberra?"

Robert G. Bailey replied:

"Maybe these "penny dreadfuls" and comics, I don't know. But I would assume the legislation which is being considered by the Attorney-General's Department, in common with a lot of other legislation, would stop up the "rat holes", as we call them."

Byrne noted there was little being published within the Territory, so a focus on the distribution and circulation of material rather than its production would be more effective.

Arthur Shakespeare clarified exactly the type of publications the Advisory Council was discussing:

"I feel that we are apt to deal with intangibles in these things. We refer to "indecent publications" and "obscene publications", and we don't mean that at all. We mean publications that are objectionable, which could not be classed as obscene or indecent but having a little edge on them which is undesirable, particularly having regard to the age of the persons into which hands they come."

Shakespeare concluded the aim was to "...know what we want to stop, and we don't want to find that having done this, everybody can go and get it at the National Library."

He then proposed that Council Members Mary Stevenson, William Byrne and Frederick Quinane examine several Canberra newsagencies to see what "objectionable" publications were on sale.

- Check by Advisory Council on Doubtful Literature. The Canberra Times, 10 August 1954, p.1: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2913528

"Now, What is the Difference?"

The Advisory Council members reported on their findings during the meeting on the 30th of August 1954. Stevenson stated that the newsagent she spoke with had voluntarily removed several publications when he took over the business, and would not sell them. The newsagent blamed the distributors who pushed newsagencies to sell these publications.

Stevenson also relayed the newsagents' comments on some of the adults who purchased comics and a potential double standard when it came to advertisements:

"He told me one very extraordinary thing: he said quite a lot of New Australians bought comics - I mean, good ones - some of them, "Knights of the Round Table" and all that sort of thing, and others, just "Bad Men" and rubbish, trash, but they could follow the thing and apparently enjoyed that."

"He also pointed out that you could get the very self-same things in advertisements as you get in many of the publications that were being talked about and were banned. You know how extraordinary some of the ads for certain things are. And he just displayed two of them for comparison, one of the books and one an ad in a perfectly respectable journal and he said "Now, what is the difference?"

Byrne reported that he had found a number of publications, banned in Queensland, on sale in Canberra:

"I have had a look in some of the Canberra newsagents and I found in the first one that they had five of these publications which had been banned in Queensland as being unsuitable for distribution - that is, "Carnival", "Festival", "Zowie", "Peep" and "Quiz". They were all being sold at one of our newsagents."

Byrne also noted that these types of objectionable publications were recent phenomena:

"It seems that it is only since the war that this question of objectionable comics on a grand scale has been exercising people's minds."

Byrne recommend that the ACT establish its own Literature Review Board similar to that in Queensland. He believed it "to be much more effective than old type of proceeding through the Police Offences Act." Debate was adjourned to the next meeting.

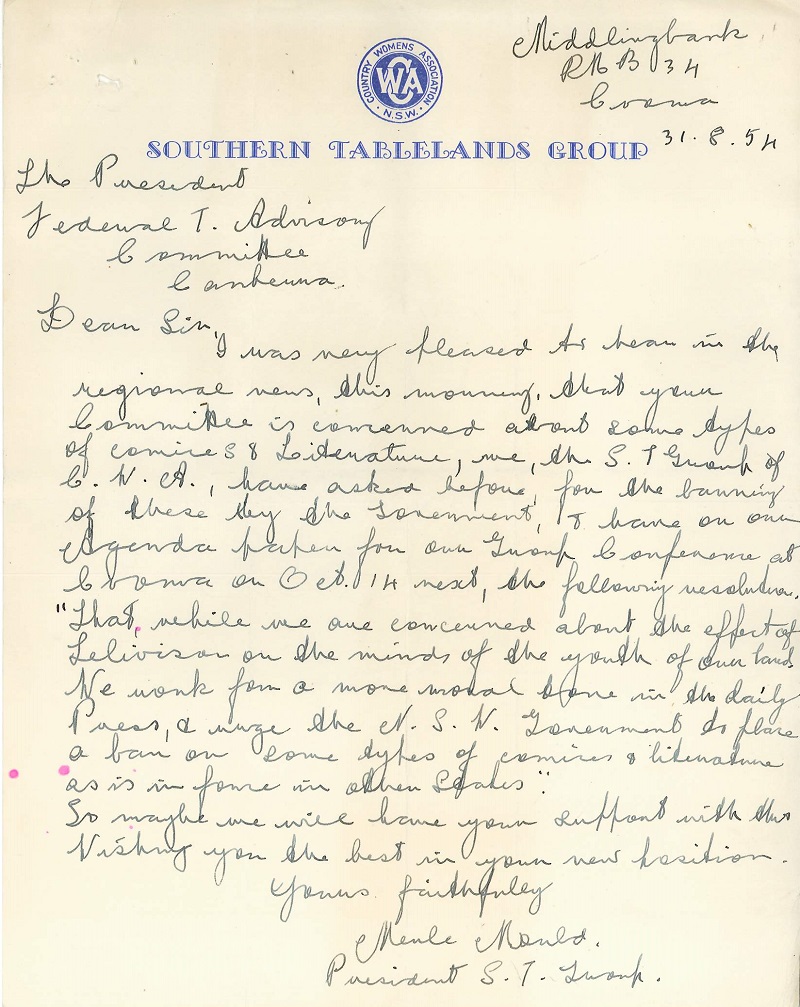

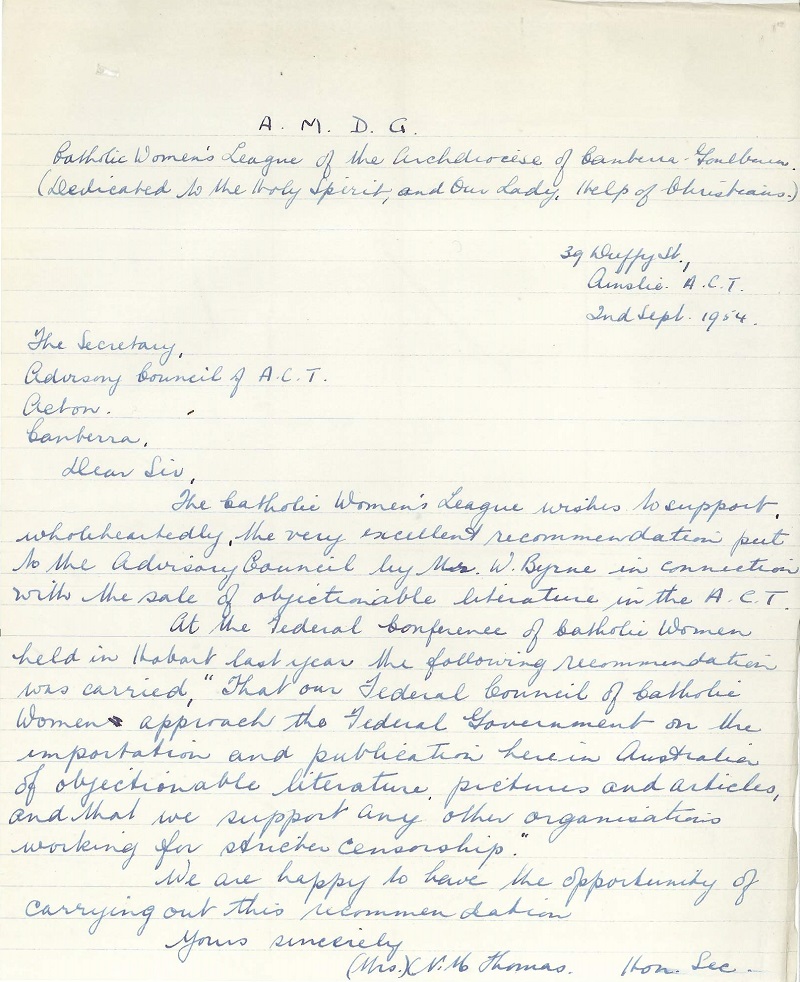

Following reports in the Canberra Times on the debate, the Advisory Council received letters in support of the Ordinance from two local women's groups:

Southern Tablelands Group of the NSW Country Womens Association. Read transcript.

Catholic Women's League of the Archdioscese of Canberra-Goulburn. Read transcript.

"To Protect the People of this Territory"

During the 20th of September 1954 meeting, Council members vigorously debated the merits of both the Queensland and NSW Acts. Byrne maintained that a Queensland-style review board was the best model for Canberra, while Shakespeare supported the adoption of the NSW Act. Shakespeare pointed out a major flaw if the ACT's Ordinance was not similar to NSW's Act:

"If the Queensland Act were to be adopted for the ACT, it would do nothing to meet the position. All it would do would be to advertise to children what are considered to be forbidden fruit; children could then go to Queanbeyan and get it and at every railway station through which they travel on their holidays they could get the stuff."

"It is the same when an objectionable novel is publicised. It serves in Canberra to lengthen the list of applications in the Commonwealth Library where it is available for everybody to see."

Debate over the form of the ACT's legislation continued well into 1955. The minutes from these meeting highlight the key points on both legislation models:

Byrne comment during the 17th of January 1955 meeting:

"The Act in Victoria does not give the Magistrate or the Judge discretionary power to say the distributor cannot distribute a particular type of work but he is prevented from distributing at all."

"That is the main reason why I do not think the Victorian Act is suitable for Canberra. We have only one distributor here and if action were taken before a Magistrate or the Supreme Court and a decision were obtained against that distributor and it was decided to use that section of the Victorian Act, it would prevent all distribution by the only distributor of books we have."

Shakespeare comment during the 9th of May meeting:

"New South Wales and Victoria have legislated on the subject in a different way and, in my view, a more correct way. That is to say, they have stated what the law is. An offender is brought before a Court, he is tried and is dealt with. I think that must be the fundamental approach to all offences committed in this country."

"What I am pointing out is that this is not just rubber stamp legislation we are making. It gives the Courts in the Territory the right of deciding whether any book passed in NSW or Victoria is decent or not. Our court is allowed to decide, on the evidence brought before it."

"It gives a live power to the Courts of this Territory to protect the people of this Territory within the limits stated by the law."

The Advisory Council carried a motion put by Shakespeare to recommend the Attorney-General's Department prepare a draft ordinance based on the NSW Act. The Minister for the Interior, W.S. Kent Hughes, approved the recommendation in July 1955.

"Some of the Most Hopeless Literature"

The Advisory Council did not discuss objectionable publications legislation again until mid-1957 when a murder trial in Victoria had caught Byrne's attention. It was the sad case of a 14-year-old boy charged with killing his 12-year-old sister.

- Boy Tried For Murder Of Sister. The Canberra Times, 9 April 1957, p.11: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91585957

As part of the case, the youth's reading material came under scrutiny. Byrne stated, "...it appeared from the evidence that he had learned to kill by reading horror comics and cheap crime magazines."

Fellow Council member, H.A. Barrenger, listed the publications found in the boys' possession as 'End to Violence', 'Murder is my Mistress', 'The Pay Off' (Deadline Detective Series),'The Informer',' Redskin Comic' (No.4 July 1956) and 'Counterspy'. Barrenger noted that, none of these particular publications, nor substantially similar ones, was on sale in Canberra.

Discussion then turned to how to influence and guide Canberra youth and, in particular, young men towards quality literature. Byrne suggested that the Technical College establish a lending library noting:

"In my observation, some of the most hopeless literature is read by the lad who is an apprentice and has not had much of a general education in literature."

"Has No Value as Literature"

In September 1957, the Attorney-General's Department sent a draft of the 'Objectionable Publications Ordinance 1957' (PDF ![]() 864Kb) to the Advisory Council for review. The draft provided some concerns for members of the Council.

864Kb) to the Advisory Council for review. The draft provided some concerns for members of the Council.

Coincidentally, it was the same month the Department of Customs banned the English edition of 'Catcher in the Rye' prompting the National Library to remove their copies from the Library's shelves.

However, due to public pressure, the ban was short lived and resulted in a review of the Department of Customs censorship process. It was Customs Officers, not the Literature Censorship Board, who banned the novel. Despite the Board approving it for sale the following month, one ACT Advisory Council member opined that Catcher in the Rye "...has no literary merit and has no value as literature."

- Banned Book Removed From National Library. The Canberra Times, 20 September 1957, p.1: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91237833

- Banned Book To Be Referred To Literary Board. The Canberra Times, 27 September 1957, p.3: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91238493

- Cameron Seeks Explanation Of Ban On Book. The Canberra Times, 3 October 1957, p.2: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91238944

- Banned Book Released. The Canberra Times, 10 October 1957, p.10: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91239656

- Book Censorship By Board Only. The Canberra Times, 26 October 1957, p.1: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91240951

This type of incident concerned Advisory Council members Phil Day and Jim Pead. Day expressed great concern on the powers the draft ordinance gave individuals within the legal system, rather than a literature review panel, to control what an adult can read. He said:

"I consider this whole ordinance objectionable and ill-considered. I think we have to look at the objective we are aiming at. After all, what salacious or objectionable literature is there on the bookshelves of this town? If we are aiming at horror comics and such like, let us say so. But this ordinance puts the whole range of adult literature at the mercy of the Court of Petty Sessions, which to me is a thoroughly alarming situation."

"I think the general public in this community should know just what is involved in this. They are entitled to know that, in the terms of this draft ordinance, the whole range of adult art and literature is at the mercy of the magistrate and at the mercy of the policeman on the beat. Here in the ACT we pride ourselves that we are something of a cultural centre. If we pass a thing like this we shall be a laughing stock in the eyes of the whole Australian community."

Pead supported Day, believing that the draft ordinance gave police officers too much latitude and "In effect, it sets him up as an expert on obscene publications."

Byrne was also critical of some sections of the draft ordinance. He believed the ordinance gave the police powers of search and seizure way beyond the NSW Act, by allowing for the seizure without warrant of publications in bookshops, whereas the NSW legislation related only to books that were hawked on the street.

Byrne agreed that such a power was necessary when it came to street hawkers due to their transitory nature. He believed there would be no urgency to search established bookstores without a warrant. However, his views on the need for censorship remained firm.

Byrne believed that profit, not intellectual freedom, was a publisher's primary motivation in producing objectionable material stating:

"There is a terrific financial field for the sale of publications which are devoted to the present day cult of what is called the "bosom"."

He added that:

"The big press barons are doing very well out of it."

"They do not particularly care if the reading of the sort of stuff they produce induces acts of crime and rape."

The more liberal-minded Day called for scrapping most of the proposed ordinance to cover only juvenile literature, along with the establishment of a Juvenile Literature Tribunal. As for Byrne's views, Day stated:

"The thing which astounds me is Mr Byrne setting himself up as the custodian of the community's morals. His remarks savor of a queer kind of a mixture of the inquisition and some sort of flavour of clerical socialism."

On the 16th of December 1957, the Advisory Council passed a motion recommending the amendment of the ordinance to limit the police powers of search and seizure.

- Decision Deferred Oil Publications Ordinance. The Canberra Times, 2 October 1957, p.6: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91238890

- Publications Ordinance Seen As Repugnant. The Canberra Times, 22 October 1957, p.3: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91240587

- Mr Day Declares: Choice Of Literature Should Be Unfettered. The Canberra Times, 17 December 1957, p.4: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91253044

- Publications Ordinance To Be Amended. The Canberra Times, 11 February 1958, p.10: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91257550

"The Absence of Culture"

On the 10th of March 1958, the Attorney-General's Department forwarded the amended 'Objectionable Publications Ordinance 1958' to the Advisory Council. Despite the absence of a provision for a Literature Review Board, Byrne was now happy with the draft ordinance.

However, Day still expressed his disapproval:

"There is no provision for any panel of experts, but merely a provision that an inferior Court and the Police will have charge of our culture."

To which Mr James responded:

"I thought it was the absence of culture that was under discussion."

On the 31st of March 1958, the Minister for the Interior, Allen Fairhall, announced that the draft ordinance was going forward for Executive Council approval. Day, wishing to record his objection to the new ordinance, stated during the Advisory Council meeting held that day:

"I should like you to bear with me while I comment on the fact that the Minister states that the Ordinance appears to meet the Council's wishes. It may meet the wishes of the majority of the members of the Council but I would like it recorded that it certainly does not meet mine."

The 'Objectionable Publications Ordinance 1958' was Gazetted on the 9th of April 1958.

- Publications Ordinance. The Canberra Times, 1 April 1958, p.3: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91246723

Not Banned but Liable to Prosecution

Despite the fears of some Advisory Council members that the ACT would become a cultureless police state due to the ordinance, the media has few reports of its practical application. The first Canberra Times article is in 1967, where it was reported that an individual was fined $200 for possession of objectionable publications which he was selling by mail.

- In the ACT Courts. The Canberra Times, 28 September 1967, p.10: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106979444

It would be another three years before police would restrict the selling of a publication from a Canberra bookstore. In September 1970, after police visited Dalton's Garema Place bookstore, Dalton's voluntarily withdrew the novel 'Portnoy's Complaint' from sale. The book was a banned import but Penguin Books in Melbourne had published an Australian edition as a challenge to State censorship laws.

At the time, a spokesman for the Department of the Interior told the Canberra Times that the novel was not banned in the ACT. However, "...any bookseller who sells a copy would be liable to prosecution."

- 'Complaint' Has a Setback. The Canberra Time, 1 September 1970, p.1: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110458350

- No Ban on 'Portnoy' But Shop Owners Warned. The Canberra Times, 9 September 1970, p.3: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110459804

- Police Will Report 'Portnoy' Sellers. The Canberra Times, 22 September 1970, p.9: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110462042

It was a further five years before police acted on the ordinance again. In March 1977, police raided the Venus Adult Shop in Fyshwick, confiscating child pornography. The courts fined Venus Enterprises and their staff, with the offending publications forfeited to the Commonwealth.

- Police Raid ACT 'Adult Shop'. The Canberra Times, 16 March 1977, p.1: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110728643

- 12 Days to Decide Action on Venus Shop Raid. The Canberra Times, 17 March 1977, p.11: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110729008

- Court Reports - Publications Charges. The Canberra Times, 29 March 1977, p.6: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110730747

- Court Reports - Hearing Adjourned. The Canberra Times, 19 April 1977, p.12: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110733551

- Films Shown During Sex-Shop Hearing. The Canberra Times, 12 July 1977, p.8: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110854366

On the 1st of February 1984, Commonwealth Government repealed the 'Objectionable Publications Ordinance 1958' with the enactment of the 'Classification of Publications Ordinance 1983'.

Page: 1 2