Previous Find of the Month - 9/2017

September 2017

'It's all about the plumbing'

Women and jury service in the ACT

"Woman are too sentimental for jury duty" Anti-Suffrage argument

(Source: Library of Congress)

In 1962, a motion was raised in the ACT Advisory Council that women be allowed to exercise their civic duty and participate in the ACT jury process. This motion would begin a seventeen year journey that would require ongoing debate, political influence and two legislative amendments before women achieved equality in the jury process. Arguments ranged from the obscure ‘it’s all about the plumbing’, to the practical ‘women provide essential childcare services’ and the offensive ‘we wouldn’t want them to go into a wild flap’.

Representation of women in the court system was a notable issue, particularly in cases involving children or sexual assault. Arguments in the positive included the benefit of introducing a female perspective in court cases, encouraging all citizens to engage in their community and of course introducing the principles of equal rights.

The theme of the recent ACT Writers Festival “Power, Passion and Politics” resonates in this important social policy development and for this reason, records relating to the debate and amendments to legislation to allow women the right to participate in jury duty are ArchivesACT’s September Find of the Month.

Do the local motion with me…

Juries Ordinance 1932 (Source: ACT Legislation Register)

In the early 1960s, jury service in the ACT was defined under the Juries Ordinance 1932 which stated that only adult males of European descent could serve on a Jury. Until this time, there had been very little public debate around the benefit of women participating in the jury process. However, in 1958 the Social Science Research Council of Australia commissioned a ground breaking survey exploring the ‘status, social and political roles of women in Australia’. Prepared by eminent sociologist, Norman McKenzie, the resulting report Women in Australia was completed in 1962, offering a comprehensive look into the role of women in the Australian legal system.

When the ACT Advisory Council met in September 1963, Councillor Professor Heinz Arndt cited this study when he initiated a discussion recommending women be given equal representation in jury service:

…Jury service is a social duty as well as a right, and though it might be inconvenient, arduous and sometimes unpleasant, while the system is maintained it is farcical and false to pretend that juries are representative of the lay community if women are excluded or their representation on the jury list diminished…

Whilst jesting that as a professor, he himself would never experience the privilege of participating in the jury process, Arndt kicked off the argument by stating that the ACT was behind the times as four states already admitted women to jury service. He reminded the Council that Tasmania, New South Wales and Queensland allowed women to volunteer for jury duty, and that Western Australia treated men and women as equals in the process. He then put forward the following motion for consideration:

Council advises the Minister to request the Attorney-General to amend Section 5 of the Juries Ordinance so as to confer qualification and liability to jury service in the ACT on women as well as men.

Professor Arndt’s motion divided the room and a healthy debate ensued between Arndt and the other seven councillors serving on the ACT Advisory Council at this time.

ACT Advisory Council, Canberra - 23.10.1964

(Source: National Archives of Australia: A7973, INT790/2)

The motion was quickly seconded by Ms Ann Dalgarno, who mentioned that this question was often asked by international visitors and the reply was always the same “It is all a matter of plumbing because juries need to be locked up for the night etc…”. Dalgarno argued that in this modern age, bathroom facilities were less of a concern and the principle of equal representation deserved more serious consideration. In today’s world, this might seem a ridiculous argument. However, Arndt pointed out this had long been used as the single most important reason given against women serving on juries. The irony, he countered, being that women prisoners and witnesses seemed to be accommodated without any issues in the court system. Despite Dalgarno and Arndt’s best attempts, some of the councillors felt that the issue of facilities merited further discussion, questioning the practicality of women serving “at a particular time” and the undue hardship this medical consideration might pose.

Hardship was the key argument of those opposed to the motion. Hardship to women who would require medical care, hardship to mothers who would have difficulty being called into service given their homely duties, and hardship to their feminine natures due to the distasteful content that they may have to contemplate as part of a jury. One councillor questioned a women’s capacity to participate when they were so consumed by their domestic duties, stating that “we are attempting to impose something on the ladies of the city which I don’t think they would want”.

The debate soon turned from all women receiving equal rights to representation within the court to the suggestion that only professional women, who would like to volunteer, could put their names down to be called upon for certain cases which would allow “a woman’s sympathy and understanding and knowledge of her sex to be used very advantageously on many occasions”. One councillor raised a recent case where two young girls were involved and with no female representation on the jury the process was made more uncomfortable for all concerned. The opportunity to increase the pool of professional jurors proved tempting to all involved as they quickly agreed that a shortfall of availability was causing issues in the courts. One councillor stated that he would prefer a qualified woman to an unqualified man any day.

After consideration of the hardship arguments, and taking into account that enlarging the jury pool would be beneficial, Mr Travis Harrison proposed an amendment to the original motion as follows:

That women be allowed to serve on juries on a voluntary basis.

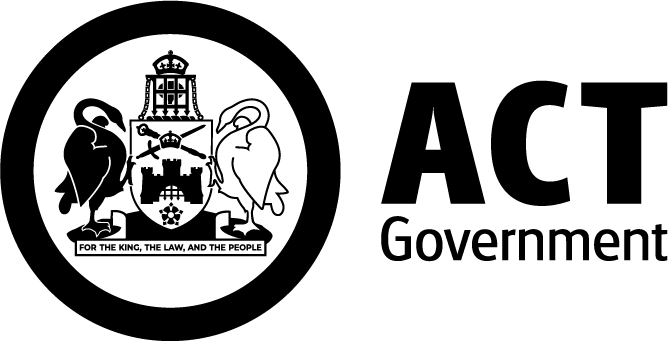

The Amendment was put and lost on a show of hands. The Motion was put and carried, and a letter recommending the amendment of the Juries Ordinance 1932 was sent to the Minister for the Interior, Mr Gordon Freeth on 25 October 1963.

Letter from the ACT Advisory Council (Source: 1964/8)

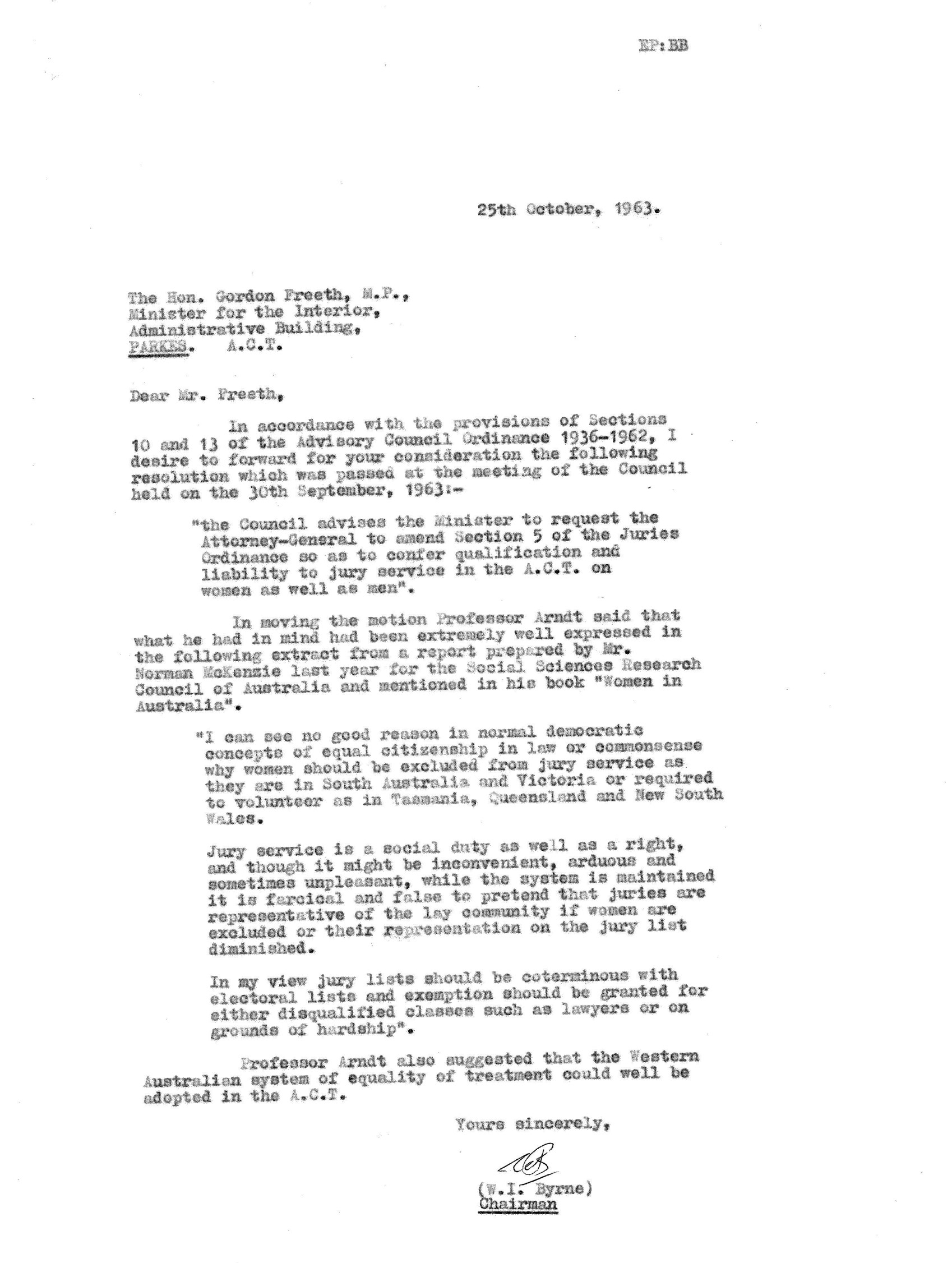

Attached to this letter was a second letter in support of the motion from the National Council of Women. As a representative on both councils, Ms Rose Andrew updated the ACT chapter of the National Council of Woman and a vote was taken in support of the motion. Of the 60 women present, representing 52 organisations between them, 100% voted in favour of the motion.

Letter from the National Council of Women (Source: 1964/8)

Meet me in the middle

Unfortunately despite the recommendations, the Minister dismissed the letter put forward by the Council of Women, stating that as there was no clear indication as to the wishes of the women of the ACT he was loathe to impose jury service on them. He did however, request that the option of voluntary service be explored and expressed his strong opinion that the discussion on ‘plumbing facilities’ was unacceptable as an excuse to delay proposed amendments.

Letter from the Minister for the Interior (Source: 1964/8)

On the 24 December 1963, the Council forwarded the following amended motion to the Minister:

That this Council advise the Minister to amend the Juries Ordinance so as to permit women to volunteer for jury service in the Australian Capital Territory.

The motion was forwarded to the Attorney-General for action and a response was received to the affirmative in March 1964. He stated there were no objections to women volunteering for duty provided that they qualified on the same grounds as men. That is, they are: adult, mentally sound and of good character. It would however, take another two years before the amended legislation was circulated back to the Council for comment.

With the turnover of councillors, a heated debate again ensued. The possibility that a jury could consist solely of women was considered and hardship arguments were once again raised. ‘Good character’ was deliberated, and one councillor insisted that a woman getting a jury notice would go into a ‘wild flap’, provoking disdain from the female councillors. The potential deterrent effect of making the process more onerous for women wishing to participate was also debated. Some councillors felt that complicating the process would help ensure that only professional women would be drawn to the opportunity, which was exactly the type of woman they preferred for jury service. Furthermore, the fact that women must apply and be approved in advance meant that they were not eligible to apply for disqualification on the day, saving time and costs by ensuring that once selected they would have to serve. Eventually it was agreed that the changes could go ahead as presented to enable the Council to focus on other changes deemed of higher priority.

Juries Act 1967 (Source: ACT Legislation Register)

The Juries Act 1967 was eventually released allowing women of the Territory to volunteer for jury duty. The first women were called to serve on the 29th April 1968.

I am, you are, we are Australian

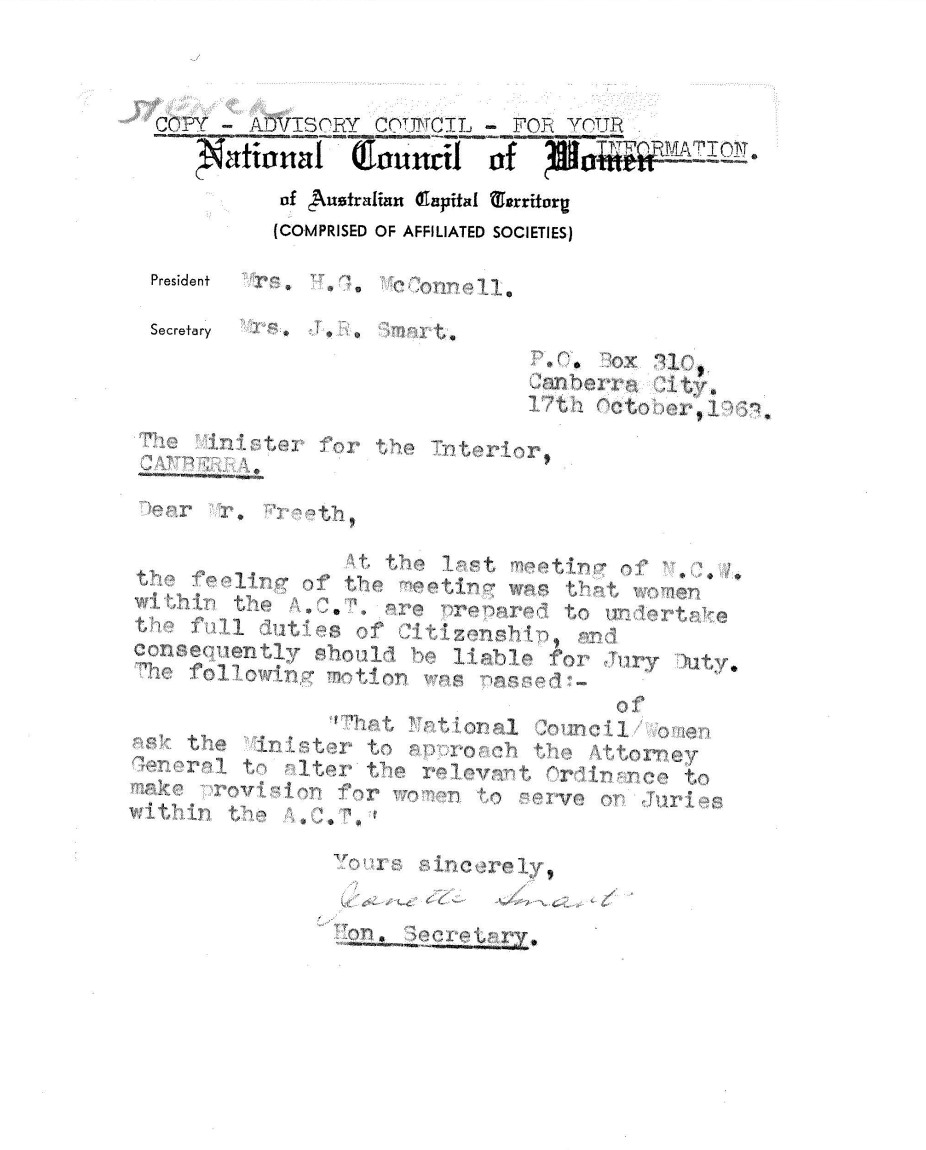

While the new legislation allowed women to become more proactive in their civic responsibilities, the onus was still on them to actively volunteer for service. It would be another decade before the legislation was once again addressed. In 1979 the Attorney-General approved an amendment to the Juries Act 1967 which finally abolished ‘any distinction between the liability of men and women for jury service’.

Letter from the Minister for the Capital Territory (Source: 79/2303)

The Juries (Amendment) Act 1979 came into effect on 1 February 1980. Being born female was no longer a valid reason to not participate in the jury process and as a result, the rules binding and/or exempting men in relation to jury service were also changed. With no distinction made between the sexes, the process was simplified and men were now equally able to access exemptions in recognition of their changing roles and responsibilities in the family home. While it may have taken many years for the ACT administration agreeing to grant full equality in this legislation, the end result would appear to be positive for all of its citizens.

ArchivesACT hopes you have enjoyed this look into the development of legislation allowing women to participate in the jury process in the ACT. If you were involved in the public debate, or actively volunteered for jury duty, why not tweet about it and don’t forget to include @ArchivesACT.

If you are interested in finding out more about these records relating to jury duty in the ACT, please contact ArchivesACT through our “Request a Record” service.

To view the original documents you can also contact us to arrange a suitable time to visit the Archives ACT Reading Room located on the top floor of the Woden Library.

Files Used

- 1964/8 – Juries and Jurors

- 79/3203 – Juries (Amendment) Ordinance 1979

Photo Credits

- National Archives of Australia: A7973, INT790/2

- Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011660530/

Links to ACT Government Websites

- Juries Ordinance 1932 (Cth): http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/ord/1932-25/19321201-48877/pdf/1932-25.pdf

- Juries Act 1967: http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1967-47/19680101-44861/pdf/1967-47.pdf

- Juries (Amendment) Act 1979 (Cth): http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1979-39/default.asp

Links to News Articles

- House Agrees To Women On W.A. Juries (1954, July 29). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved August 31, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52957923

- LIFE STYLE (1974, August 7). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 17. Retrieved August 28, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110722653

- Review of ACT jury system (1967, February 16). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 3. Retrieved August 28, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106962490

- Women For Juries Move Supported (1963, October 1). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 6. Retrieved August 28, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article104269281

- Women jurors called in ACT today (1968, April 29). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 1. Retrieved August 28, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article107048948

Links to External Websites

- NLA (2017). Catalogue Results http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/209604384?q=norman+mckenzie+women+in+australia&c=book&versionId=230021143

Previous Find of the Month

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

File Readers/Viewers

If you do not already have compatible software on your computer, free file readers/viewers can be downloaded from the following links.

PDF files require Adobe Acrobat Reader

PDF files require Adobe Acrobat Reader PPS files require Microsoft PowerPoint Viewer

PPS files require Microsoft PowerPoint Viewer XLS files require Microsoft Excel Viewer

XLS files require Microsoft Excel Viewer Word files require Microsoft Word Viewer

Word files require Microsoft Word Viewer