Previous Find of the month - 4/2017

April 2017

Facilitating Change:

In support of a unified approach to gun control

Port Arthur Memorial (Source: Ashley, 2009)

In April 1996 the actions of a lone gunman, in Port Arthur, Tasmania, saw Australia reeling from its worst ever massacre. The senseless death and destruction wreaked on innocent lives caused a public outpouring of grief, followed by outrage, heated debate and the eventual introduction of strict gun control laws.

At this time the fledgling ACT Government had already introduced tough new gun control laws through the Weapons Act 1991, however, the less restrictive approach of the other states made these hard to enforce. The debate that was to follow the tragedy allowed the ACT Government to have a proactive role in encouraging bipartisan support for change on a national scale.

Records covering the development of the ACT's gun control laws and our contribution towards the national debate are now 20 years old and open for public access, making them ArchivesACT's Find of the Year.

Ripe for Change

The Port Arthur massacre in 1996 was undoubtedly the bloodiest such incident to occur in our recent history, with a total of 35 people killed and another 23 wounded. Sadly, it was not, however, one of a kind. In the ten year period prior to Port Arthur we experienced eleven massacres in Australia, many of these involving the use of semi-automatic weaponry, including three well-known mass shootings:

- Hoddle Street massacre - 7 dead, 19 wounded

- Queen Street massacre – 9 dead, 5 wounded

- Strathfield massacre – 8 dead, 6 wounded

In 1996, gun control legislation was managed by the individual states, with Commonwealth legislation restricted to control of the import of firearms via the Customs Regulations 1956.

Immediately after the Port Arthur massacre the anti gun sentiment that had been slowly building in response to these increasingly violent incidents finally reached a boiling point. Two prominent anti-gun organisations, the National Coalition for Gun Control (NCGC) and Australian Gun Control (AGC) increased their lobbying for unified changes to legislation, with the NCGC even being recognised for an Australian Human Rights Award for this work in 1996.

It is important to note that while anti-gun sentiment ran high in urban Australia, many people from regional Australia were concerned that their rights as responsible gun owners were being curtailed. Farmers were joined by sporting shooters and hunters who organised rallies to protect their rights to acquire and use firearms.

Up until this incident, the Federal Government had prevaricated when engaging in the gun control debate. However, in 1996 there was a change of government, and the newly elected Prime Minister John Howard was an anti-gun advocate who had revealed his stance whilst Leader of the Opposition in 1995:

Whilst making proper allowance for legitimate sporting and recreational activities and the proper needs of our rural community, every effort should be made to limit the carrying of guns in Australia.

The combination of this horrendous incident, the subsequent shift in public opinion, and a newly elected government provided an opportunity for the Federal Government to push for comprehensive legislative changes on gun control in Australia.

Closer to Home

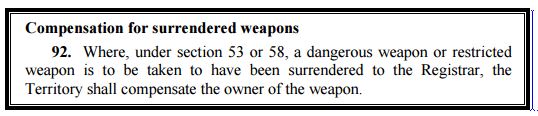

In 1991 the still-new ACT Government was already taking steps to address the issue of gun control in the region. Although the government recognised that there would always be some risk of illegal weaponry, it hoped that with new legislation the risk of a mass shooting would be significantly reduced. The Weapons Act 1991 was arguably Australia’s most restrictive gun control legislation to date and was supported by all the political candidates in the lead-up to the 1992 elections. This legislation was unique in that it included a rigorous screening process which made it more difficult to be granted a licence, ensured that all owners and guns were registered, included substantial fines for breaching the Act, and categorised weapons as dangerous, restricted and prohibited. All fully automatic and military style semi-automatic weapons were listed as prohibited and were able to be confiscated under the Act with compensation paid to their owners.

Extract from the Weapons Act 1991 (Source: ACT Legislation Register)

Whilst the ACT Government was proactive in getting its own house in order, the rest of Australia maintained a mixed approach, with some states not even requiring screening for licences or registrations for the purchase of firearms. This inconsistent approach made enforcing the ACT legislation difficult. In 1992, following the Strathfield massacre, the Attorney General of the ACT, Terry Connelly, and the former Attorney-General, Bernard Collaery, joined together to call for the unification of Australian gun laws with Connelly arguing that:

Nothing will stop people from bringing guns across the border. It will be illegal to possess them in the ACT, but we can't have border posts to inspect vehicles coming across from Queanbeyan. That would be absurd.

Mail orders also compounded the problem as a weapon could be legally ordered from another state, effectively bypassing ACT gun controls.

In 1995, the debate on a unified approach to gun control took centre stage when the Australasian Police Ministers Council announced the formation of a working group. The ACT Government once again offered its support with ACT Police Minister Gary Humphries stating that “the ACT Government takes very seriously a responsibility to promote national gun control and safety”. Unfortunately before any recommendations could be made and implemented, the incident at Port Arthur occurred.

First in line

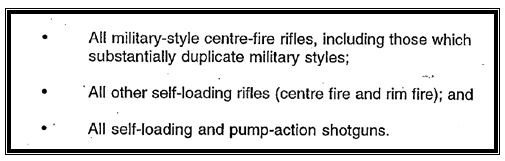

The Federal Government responded to the Port Arthur massacre with bipartisan support by convening a special meeting of the Australasian Police Ministers’ Council (APMC) in May, 1996. The outcome of this meeting was ten key recommendations, the most significant of which was the prohibition of the ‘importation, ownership, sale, resale, transfer, possession, manufacture or use of the following semi-automatic firearms:’

Extract from the minutes of the Special Firearms Meeting 1996 (Source: 96/12164)

Another recommendation proposed an amnesty for the surrender of firearms in the form of a gun buyback . The ACT moved quickly to adopt these recommendations in to support long-desired uniformity and to make Australia ‘a safer place’. This required amending the Weapons Act 1991 to form the Weapons (Amendment) Act (No. 2) 1996. In practical terms the Act required very few changes, as the ACT’s previous diligence meant that licensing and registration requirements were already in place. Aside from some minor language amendments, the only other major change was the broadening of terms in the weapons schedule to encompass all semi-automatic weapons, not just military style firearms.

To prepare for the upcoming gun buyback, arrangements for compensation were also amended in the Territory’s Act with an adjustment made to ensure that compensation would not be payable for firearms that were already prohibited. This would ensure that only legally held items would be financially compensated when surrendered.

Media coverage of the APMC meeting on 10 May 1996,

Parliament House, Canberra (Source AFPM10184)

A Unified Front

Over the next few years, the Commonwealth introduced three key agreements to strengthen the unified approach on gun control:

- National Firearms Agreement (1996)

- National Firearm Trafficking Policy Agreement (2002)

- National Handgun Control Agreement (2002)

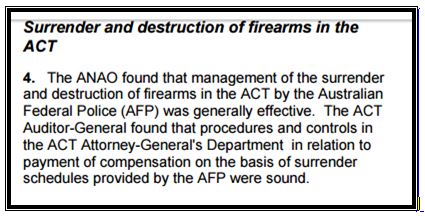

The National Firearms Agreement 1996 was based on the recommendations of the APMC and was rolled out in conjunction with the National Firearms Program Implementation Act 1996 which provided funding from the Commonwealth Gun Buyback Program to the states on the condition that they first sign up to the unified agreement. Under this scheme it is estimated that approximately 700,000 guns were surrendered around Australia and destroyed. In the ACT, residents could return their guns to the City Police Station and unverified statistics suggest that over 5000 guns were returned locally through the scheme. The ACT was used by the Australian National Audit Office to assess the success of the gun buyback and the government’s efficient processing was viewed positively:

Extract from the ANAO Gun Buyback Scheme Report (Source: Online)

Leading the way

Although the outcome of these stricter gun control laws has been hotly debated, what is evidenced by these records is that the ACT’s ability to be at the forefront on difficult social issues. Canberra has sometimes been referred to as a social experiment. Its small geographic size, single level of government, and relatively progressive, well-educated population sometimes make it possible for Canberra to achieve things that may be much harder to do elsewhere. The 1996 changes to gun control are a compelling example of where Canberra was able to lead significant change on difficult issues.

Guns were returned to the City Police Station, Canberra (Source: Bidgee, 2009)

If you would like a copy of this record please contact ArchivesACT through our “Request a Record” service.

If you would like to view the original documents you can also contact us to arrange a suitable time to visit the Archives ACT Reading Room located on the top floor of the Woden Library.

Files Used

- 96/12164 – WEAPONS (AMENDMENT BILL NO. 2) 1996 – PROHIBITION OF SEMI-AUTOMATIC WEAPONS

Links to News Articles

- ACT's new gun laws 'Aust's most advanced' (1991, August 20). The Canberra Times, p. 2. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122378797

- Gun-hiders to join rally (1991, September 20). The Canberra Times, p. 5. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122385324

- I have never done anything illegal in my life: owner 'Killer' weapon offered for sale (1991, August 25). The Canberra Times, p. 3. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122379832

- Mike Taylor investigates the shortcomings of recently introduced firearms legislation. Gun laws back in spotlight again (1992, October 29). The Canberra Times, p. 11. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article126952347

- Tough gun laws highlight parties' similarities (1992, February 13). The Canberra Times, p. 9. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133930634

- Toughest gun laws likely soon for ACT (1991, February 15). The Canberra Times, p. 3. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article129096271

- Uniform gun laws under spotlight (1995, May 27). The Canberra Times, p. 2. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article130553644

Links to ACT Government Websites

- Weapons Act 1991 (ACT): http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1991-8/default.asp

- Weapons (Amendment) Act (No. 2) 1996 (ACT): http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1996-18//

Links to External Websites

- Australian National Audit Office(1997). The gun buyback scheme: https://www.anao.gov.au/sites/g/files/net616/f/anao_report_1997-98_25.pdf

- Australasian Police Ministers Council (1006). Special firearms meeting: https://www.ag.gov.au/CrimeAndCorruption/Firearms/Documents/1996%20National%20Firearms%20Agreement.pdf

- Customs Regulations 1956 (Cth): http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_reg/cir1956432/sch6.html

- Firearm Owners Association of Australia (n.d.). Buy-back statistics and Australia's stock of firearms 1998: https://www.foaa.com.au/ammunition-to-send-to-politicans/buy-back-statistics-and-australia-stock-of-firearms-compiled-in-1998/

- Gun laws in Australia (2017): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gun_laws_in_Australia#Major_players_in_gun_politics_in_Australia

- Hoddle Street massacre (2015): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoddle_Street_massacre

- Howard, John (1995). The role of government, 1995 Headland speech: http://australianpolitics.com/1995/06/06/john-howard-headland-speech-role-of-govt.html

- Lauder, Simon (2015). Call for national gun amnesty amid police concerns: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-19/call-for-national-gun-amnesty-amid-police-concerns/6559158

- National Firearm Trafficking Policy Agreement 2002: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2004A01078

- National Firearms Agreement 1996: https://www.ag.gov.au/CrimeAndCorruption/Firearms/Documents/1996%20National%20Firearms%20Agreement.pdf

- National Firearms Program Implementation Act 1996 (Cth): https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2004A05054

- National Handgun Control Agreement 2002: https://www.ag.gov.au/CrimeAndCorruption/Firearms/Documents/2002%20National%20Handgun%20Agreement.pdf

- National Museum of Australia (2016). Port Arthur massacre: http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/port_arthur_massacre

- Queen Street massacre (2017): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_Street_massacre

- Strathfield massacre (2017): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strathfield_massacre

Photo Credits

- Ashley (2009). Port Arthur Memorial. Retrieved from Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/78821753@N03/22461121816/in/photolist-AdP7YY-d9ggHo-jE872g-5am39M-oHHtfc-61dic8-jE9dsR-84VqAx-e7Dm6D-6LXnL5-ALmJG-oHFDyj-7APD39-nWcDKa-nu88Cj-pH1CV9-e3U9Gp-fCL9gH-i3iFVy-i3iyiu-qY9N7X-i3izgd-iWv3s-7C7eEp-6LTcKg-jE9qU5-qNju9i-vhzec-4Fvs5o-kkZ8R-dpjSfY-7ECv3h-k4Hvx9-6vZdeB-qNju9D-e6ozU1-k4FJXt-9tDyfM-tqcX-4Kq9wT-U2h54-bWTn3T-jE8vcg-9vewT1-d9gf2S-9NdAFi-n5TTr6-nERGBp-8o7qxZ-7yU4AM

- Australian Federal Police Museum (1996). Media coverage of the APMC meeting from file AFPM10184. Reproduced with permission. Copyright AFPM.

- Bidgee (2009). City Police Station in City, Australian Capital Territory. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:City_Police_Station_in_Canberra.jpg

Previous Find of the Month

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

File Readers/Viewers

If you do not already have compatible software on your computer, free file readers/viewers can be downloaded from the following links.

PDF files require Adobe Acrobat Reader

PDF files require Adobe Acrobat Reader PPS files require Microsoft PowerPoint Viewer

PPS files require Microsoft PowerPoint Viewer XLS files require Microsoft Excel Viewer

XLS files require Microsoft Excel Viewer Word files require Microsoft Word Viewer

Word files require Microsoft Word Viewer